By Akram al-Waara for Middle East Eye

Aisha Abu Awwad was up at the crack of dawn on 7 July, ready for her usual morning routine.

She let her sheep out of their pen, hung some washing up to dry, and began preparing breakfast for her family of 12 on the gas stove outside their tent.

But at around 9am, the familiar sounds of the wind rustling through the al-Bqai’a plains of the Jordan Valley, and of the sheep grazing nearby, were disrupted by another familiar sound – one that sent chills down Aisha’s spine.

“We heard the sounds of the military jeeps approaching, and when I looked out onto the horizon, I saw that there were dozens of them coming towards us,” Aisha, 56, told Middle East Eye.

The sight of Israeli military jeeps, bulldozers, and civil administration vehicles approaching her village of Khirbet Humsah, in the occupied West Bank, was a terrible, yet familiar sight to Aisha. It’s a scene that she had witnessed and relived six times over the past nine months, and one that she knew did not end well.

She immediately began waking up her sleeping grandchildren, as her husband and sons began rounding up their livestock.

“When the kids saw the jeeps they became frantic and started screaming and crying,” Aisha recounted. “They kept saying, ‘Grandma, grandma, they are coming to destroy our homes!’”

There was little Aisha could do, however, to calm her grandchildren down. Just minutes later Israeli soldiers began rounding the family up along with their neighbours, and throwing them out of their homes.

Aisha and her family are one of 11 Palestinian families, consisting together of more than 70 people, who reside in the small Bedouin hamlet of Khirbet Humsah, which has been subjected to a campaign of repeated demolitions by Israel.

Between November and February, Aisha’s family’s homes and livestock pens were destroyed six times. On that hot July day, they were faced with their seventh demolition in less than a year.

‘This is what they do to our children’

“When they first came in November, they left us out in the cold and rain with no shelter,” Aisha said, noting that her youngest granddaughter was only three months old at the time.

“This time, they left us out in the hot sun, with no food, water, or anything to protect us from the heat,” she added. “They told us we were there illegally, and that we needed to leave. Then they just started destroying everything.”

As Aisha sat alongside her young grandchildren in the hot sun, watching her whole life being destroyed in front of her eyes, she said she felt helpless.

‘They come here every time and destroy our lives, and we can’t do anything to defend ourselves. We are just trying to live a simple life with our livestock and our children. Is that too much to ask?’

– Aisha Abu Awwad

“They come here every time and destroy our lives, and we can’t do anything to defend ourselves,” she said. “We are just trying to live a simple life with our livestock and our children. Is that too much to ask?”

According to reports from the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), Israeli forces completely cleared out the area where Khirbet Humsah had stood, demolishing and confiscating items such as water tanks, animal troughs and children’s toys, as well as several structures that had been donated by international humanitarian aid organisations.

“They took everything, they didn’t even leave us our clothes, or the diapers and formula for the babies,” Aisha recounted. “We slept out in the middle of the open fields that night with the kids, without any blankets or even mattresses.”

“The repeated destruction of their homes and property, including assistance provided by the humanitarian community, is having a devastating economic, social and traumatic impact on the community, particularly children,” OCHA wrote, adding that Israeli forces had prevented aid workers from reaching the community in the aftermath of the demolition.

Aisha’s grandchildren, seven of whom are under the age of 10, are among the 41 children who live in Khirbet Humsah. She said that her grandchildren are now sleeping in the same tent as her sheep.

“This is not safe or healthy for the children,” she said. “But this is the reality of the occupation, this is what they do to our children,” she said.

‘Facts on the ground’

Khirbet Humsah is one of hundreds of Palestinian communities in Area C – the more than 60 percent of the West Bank under full Israeli security and civilian control, where Palestinian construction is largely banned.

Within Area C, thousands of acres of land have been cordoned off by Israel and designated as closed military zones and “firing zones”, where the army routinely conducts training exercises using live fire and explosives.

According to OCHA, firing zones cover nearly 30 percent of Area C, encompassing around 38 Palestinian Bedouin and herding communities, with a population of 6,200 people. More than a third of those communities live in the strategic Jordan Valley.

OCHA has described these communities as “some of the most vulnerable” in the entire West Bank, due to their restricted access to education, basic health services and infrastructure.

On top of that, Israel routinely serves these communities with home demolition orders and orders to evacuate their homes during military training exercises, which can last for days at a time.

Since 2012, OCHA has documented over 50 incidents in which residents of Khirbet Humsah were kicked out of their homes during military training activities.

Rights groups argue that the designation of such firing zones, and the demolitions and forced evacuations that occur as a result, are a cover for the Israeli government’s plans to annex large swaths of land in Jordan Valley in violation of international law.

‘We are just trying to live a simple life with our livestock and our children. Is that too much to ask?’

– Aisha Abu Awwad, Khirbet Humsah resident

“They aim to establish facts on the ground and take over these areas so as to establish conditions that would facilitate their actual annexation to Israel as part of a final status arrangement, and until that time, annex them de facto,” Israeli human rights group B’Tselem has said of the situation in the Jordan Valley.

“This is a very important and strategic area for the Israelis,” Moataz Bisharat, a local activist in the Jordan Valley, told MEE. “Israel has been very clear about its plans to annex the Jordan Valley, so people should not be surprised when it comes and destroys Khirbet Humsah time and time again.

“All over the Jordan Valley, you will not only find firing zones, but military zones, national parks, state lands, etc,” he added. “These are all designations used by the state in order to take over more land.”

Clearing the way for settlements

Just 2km away from Khirbet Humsah are the Israeli settlements of Bekaot and Roi. In stark contrast to the tents and tin structures of Khirbet Humsah and other Bedouin hamlets nearby, the settlements stand out like small green oases in the dry and arid summertime landscape – with bright stone homes and red rooftops, electricity lines, lush trees, children’s parks, and large plots of land filled with greenhouses.

“If you want the most stark example of Israeli apartheid in practice, you don’t have to look any further than right here,” Bisharat said, pointing to the direction of Bekaot.

“These settlements are built on stolen Palestinian land. The settlers are given running water, electricity networks, roads, homes, greenhouses, and land to farm,” he added. “Their entire lifestyle is subsidised by the Israeli government.”

Just a five-minute drive away, Bisharat pointed out, the Palestinians of Khirbet Humsah are offered none of these services, and are criminalised for living there.

“The Palestinians have papers to prove ownership over this land, and were here even before the state of Israel was created,” Bisharat said. “But according to Israel, only the settlers have the right to live here, even though their settlements are illegal under international law.”

Israel is seeking to move the Palestinian residents of Khirbet Humsah to another area of the northern Jordan Valley called Ein Shibli, a move rights groups say would amount to forcible transfer, a war crime under international law.

Residents of the small village say that Ein Shibli, a more urban area, is not suitable for their lifestyle, and would present a number of issues for them if they were to move there.

‘If they kick us out and move us to Ein Shibli, we are not just losing our homes, but our livelihood as well. Our business, our livestock, our income, etc, will not survive if we leave this place’

– Mohammed Abu Awwad, resident of Khirbet Humsah

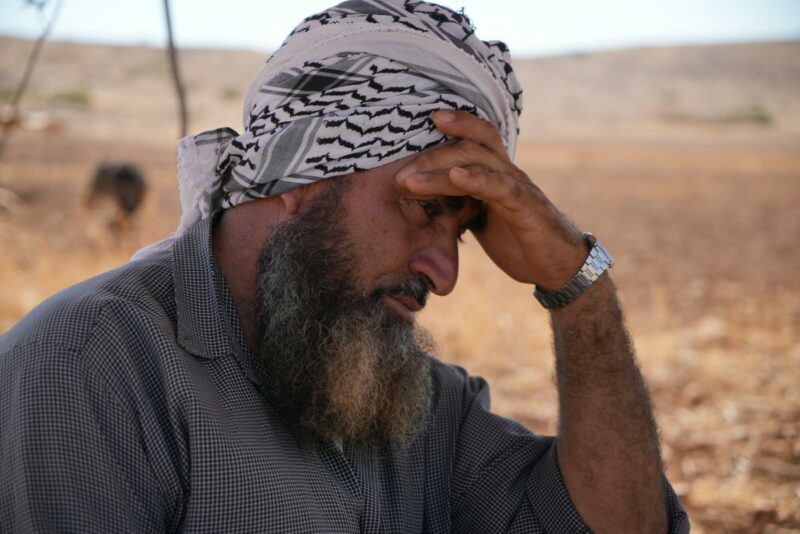

“They are trying to cheat us,” Mohammed Abu Awwad, another resident of Khirbet Humsah, told MEE. “We don’t know the place [Ein Shibli], we don’t have land there, there’s no space for our animals to move through the mountains.

“One of the main reasons we live here in Humsah is because of how good it is for our animals,” he added, pointing to the sprawling plains around him, which he said were perfect for grazing his livestock even in the hot summer months.

“If they kick us out and move us to Ein Shibli, we are not just losing our homes, but our livelihood as well. Our business, our livestock, our income, etc, will not survive if we leave this place.”

While the Israeli government claims that moving communities like Khirbet Humsah to “permanent sites” like Ein Shibli is done with the aim of “improving their standard of living”, rights groups like B’Tselem say the policy is “meant to constrain the Palestinian residents to narrow confines within urban areas, thereby limiting their ability to make a living as shepherds and farmers”.

“As with most other aspects of life under occupation, plans were drawn up by Israeli authorities without consulting or involving the communities’ residents, who have no political power – or even representation as a mere formality – in the decision-making processes,” B’Tselem wrote.

Meanwhile, Palestinians say that Israeli settlers living in the Ein Shibli area are extremely violent, and routinely commit attacks on Palestinian communities there.

“We don’t want to go there,” Aisha told MEE. “We are sure that even if we do go, the Israelis will find a way to kick us out from there as well.”

‘Empty statements’

In the week since Israel destroyed Khirbet Humsah, residents of the village have managed to erect a few small tents to sleep in, and retrieved some of their belongings confiscated by Israeli forces and dumped in Ein Shibli.

Many of the families, including Aisha’s and Mohammed’s, have since been prevented from returning to the same spot where their homes once stood, and are now sitting in an area around 500 metres away.

“There are Israeli soldiers here 24/7, and they won’t allow us to go back to where we were before. If we even pass by there with our sheep, they threaten to arrest us,” Aisha said, adding that her and family’s clothes are still strewn in piles on the ground.

In the days before and after the demolition, the residents say they were visited by a number of international diplomats and aid workers who condemned Israel’s actions in Khirbet Humsah.

But the residents say they’ve had enough of “empty statements”.

“All this shows is that the international community cannot protect us,” Mohammed said. “Israel thinks it is above the law, and the international community does not do anything except issue statements.

“We want action. Don’t just come visit us and feel sorry for us – take action.”