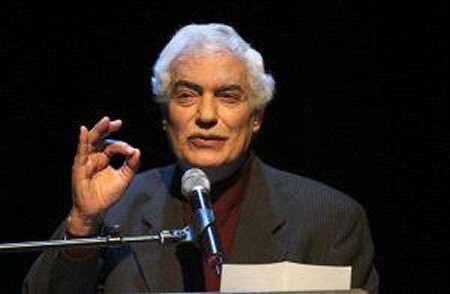

Well known Palestinian poet Ahmad Dahbour passed away on Saturday, at a Ramallah hospital, following deterioration in his health, said the Ministry of Culture in a eulogy statement, according to WAFA. He was 71.

Dahbour was born in Haifa, in 1946, and had lived in Beirut and Syria after the 1948 dispersion of the Palestinian people, following the creation of Israel on Palestinian land.

He published a number of poetry books during his life, most published in Beirut, and his poetry was used as nationalist songs by many groups.

President Mahmoud Abbas and the Palestinian government have expressed their sorrow for the death of Dahbour and sent condolences to his family.

Coffee, by Ahmad Dahbour

(Translated by Hassan Hilmy)

![]()

As the walls, in their notched neutrality, shrank

and the sky got trapped between the curtain at

the window and the sea zenith,

I watched my cup of coffee

gradually getting cooler.

Well, I must make some fresh coffee.

![]()

That was just a pretext:

the walls remain neutral

and the curtain does not reveal more of the sky.

![]()

Enter, suddenly, Tarafa bin al-‘Abd

with his hot blood and twenty-four year lifespan

He took off his head and put it down on the desk,

As a soldier would put his helmet down

on the dining board.

I examined the neck

but could find no trace of the sword blow.

![]()

Then Rimbaud came in and placed his amputated

leg

there on the doorstep

beside his thirty-seventh year.

I at once rolled half a century and ten frustrations

![]() into a ball

into a ball

and aimed a pointless question.

Which of us is the eldest?

I asked, as I was making fresh coffee.

![]()

Ibn al-‘Abd put his head back on

and told me that he was unable to get a birth

certificate.

As for bored Rimbaud,

he resuscitated the alphabet

and let fall his seventeenth year.

He soon referred me to his poem

‘Poets at the Age of Seven’.

He added: I am 37, 17, or 7,

all these are my years.

At what age, then, would you like to apprehend

me?

![]()

Now, as I drink coffee alone

![]() (cold again)

(cold again)

I put words together and they keep failing me.

I am not of Tarafa’s generation.

I am twenty-seven years older,

and he is one thousand four hundred and six

years older than me.

I know of no way to capture Rimbaud in one of

his ages.

![]()

When I drew back the curtain

the sky did not grow any vaster

and the sea was not greater than me,

for the sea was being born

from a question rubbing itself against a rock.

![]()

Alone, alone am I,

not like Tarafa’s tar-smeared camels

but like a paved road on a Tunisian summer day,

Alone, all alone with no friends of my generation,

I have no games to play

and no warm coffee.

![]()

I go into the bathroom and draw the curtain.

And as soon as the water flows

to relieve me of the dust of fatigue and confusion,

![]() I stick out my tongue at Tarafa and Rimbaud

I stick out my tongue at Tarafa and Rimbaud

and at the other guy whose features I could not

make out.

But he was born on the same day as I

in Harrari or Shanghai

![]()

It is very likely that Bill Clinton and I

were born in the same year.

Is he then of my own generation?

![]() Does ‘generation’ mean lifetime?

Does ‘generation’ mean lifetime?

Or is it the emanation of joy and pain out of the

portal of space

or out of the lash of questions?

![]()

As for the earth and the outer space,

they were fornicating in public,

and the one they could not have begotten

is me.

![]()

I, the one born not as he would have liked to be,

the one who always forgets his coffee until it gets

cold,

the one who keeps his tricks in his mirror,

hereby affirm that I have seen the people of my

generation on the streets.

![]()

![]() But how can I prove it?

But how can I prove it?

![]()