Despite Israeli authorities’ best attempts to erase history, the 1948 catastrophe is a basic component of collective memory for Palestinian citizens of Israel.

via the Alternative Information Center (A)C).

How is the memory of the Nakba sustained by younger generations of Palestinians living in Israel? Unlike Palestinians living in camps or elsewhere in exile, those living in Israel face sustained state efforts to erase this event. Yet the collective memory of 1948 is still mapping out Palestinians’ daily lives so that there is no place to ‘forget’ it – how does this happen? These questions led my research among young Palestinian citizens of Israel about their collective narrative of the Nakba.

To all Palestinians, the Nakba is a tragedy, consequences of which are felt even today. The victims are not only the Palestinian refugees, but also the entire Palestinian nation, including those who became citizens of Israel. For this minority, the disaster continues to constitute an open wound. In order to meet the challenges of their present marginalized status as second-class citizens – who are collectively excluded and discriminated against in an ethnic state that denies its non-Jewish citizens a national identity, political power, and property – Palestinians in Israel have had to develop their own collective cognitive-affective repertoire. Such a repertoire has developed to include as its basic component the collective memory of the Nakba.

Since 1948, these Palestinians’ attempts to create a coherent narrative of their collective past have often been challenged and silenced. The war of 1948 led to the disappearance of most of the Palestinian printed works and institutional memory in Palestine. Israel destroyed and confiscated all public libraries, printing presses and publishing houses, as well as land registries, municipal council archives, schools and cultural centers. In addition, depopulated houses were blown up or razed to the ground, making concrete the Zionist narrative that Palestine was virtually empty territory before the Jews arrived.

Random life stories told by individuals who have experienced the Nakba cannot by themselves create a national narrative and a collective memory with which a whole community can identify. National narratives and collective memory require institutional support for cultural products such as books, plays, and films. Palestinians in Israel do not have their own national agencies or archives through which young generations can be made aware of their collective history and memory. In addition, they face the deliberate silencing of their narrative by Israeli authorities.

Palestinian citizens of Israel are not and have never been taught about the Nakba in schools. They obtained most of their information about it via informal socializing agents such as their grandfathers, the so-called “Nakba generation” – those who lived through the war – who were one of the main sources of knowledge about what happened in 1948. This “Nakba generation” represents a “mnemonic community” made up of those who witnessed the war, experienced the expulsion and are still engaged in remembering it. This mnemonic community incorporates new members by familiarizing them with the community’s past, which they do not have to experience personally in order to remember it.

Actually, discussions about the Nakba are frequently held because of various “mnemonic arenas” that generate them. For example, the continuous occupation of the West Bank and Gaza, punctuated by occasional armed onslaughts, are constant reminders of the past.

In addition, the core of young Palestinians’ existence as unequal citizens in the state of Israel is also an unceasing aide-mémoire of the fact that their nation was defeated in 1948 and they became a minority in Israel. Therefore, it seems that their collective memory is connected to their present and future situation. As one young person put it, “Nakba is not a memory of the past, it represents our future as well…land confiscation and governmental legally discriminatory practices, such as passing the Nakba law, are part of an ongoing and persistent alarm bell that keeps me alerted, and intensifies my sense of insecurity.”

Similarly, having relatives living in the Diaspora who are unable to come back to their places of birth is also a topic that stimulates frequent discussions of the past. Ties to family and friends living in the Diaspora are maintained mainly through sentiments stemming from memories.

Another mnemonic arena that is highly significant is the country’s topography. Features such as cactus fences, fig trees, street names, old Arabic buildings and other remnants of the past always tell picturesque stories that combine smells, tastes and other senses that bring life to such stories. Finally, the land shortage, resulting from land confiscation, turned the term “land” among young Palestinians into a reminder of painful reflections of exploitation, uprooting and dispossession.

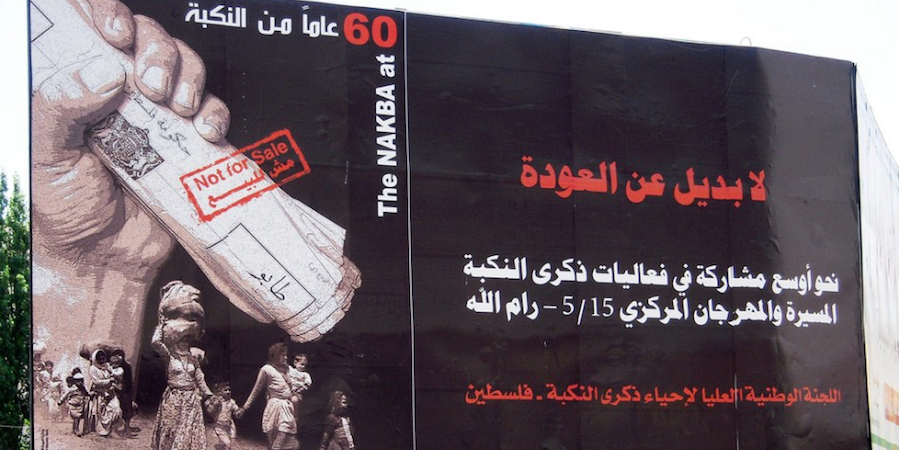

Young Palestinians are increasingly taking steps to commemorate the Nakba by participating in activities such as organized visits to the sites of destroyed villages and the preservation of remaining sites and ruins, especially mosques, churches and cemeteries. They use memorial activities as a tool to express discontent and to protest against discrimination. As one young person put it, “What happened in 1948 is tragic. It is devastating to know that even nowadays we can still find some Israeli Jewish political movements calling for Arab transfer. I’m not afraid to say that I won’t permit any further expulsion of my people, I won’t evacuate my house at any cost, even if I have to sacrifice my life for it.” They have transformed Nakba Day into a general Palestinian national memorial day so their visits to destroyed villages have taken the form of a protest against what is being done to them currently.

To sum up, it can be concluded that the collective memory of the Nakba among young Palestinians hints at various characteristics of this generation. First, a new generation of Palestinians in Israel has grown up and they have chosen to emphasize their national identity rather than hiding it. Second, this group’s growing sense of marginality in Israel has been another factor contributing to the reconstruction and rehabilitation of the Nakba memory and its narrative, which has never been erased and it is being transmitted to successive generations.

by Dr. Abu Hanna-Nahhas, Head of the Department of Education at the Teacher’s College in Haifa and serves on the board of Adalah.

This piece was originally published by The Nakba Files: the Nakba, the Law and What Lies In Between.