In 2002, the Israeli government decided to construct “a barrier” separating the West Bank and Israel with the declared purpose of improving the security of Israel by preventing Palestinians from entering Israel without first being cleared at a checkpoint. [1]Today, the Annexation and Segregation Wall consists partly of concrete slabs which are eight to nine meters high, and are connected to form a concrete wall, and, partly, of fences, ditches, razor wire, groomed sand paths, an electronic monitoring system, patrol roads and a buffer zone.[2]

The International Court of Justice (ICJ) declared, in its Advisory Opinion, on 9 July, 2004, that the Annexation and Segregation Wall and its associated permit regime is contrary to international law, and that all states are under an obligation not to render aid or assistance to maintain the situation created by its construction. [3]A particular concern of the ICJ was the location of the Annexation and Segregation Wall and the ICJ noted “that the route chosen for the wall gives expression in loco to the illegal measures taken by Israel, and deplored by the Security Council, with regard to Jerusalem and the settlements, and that it entails further alterations to the demographic composition of the Occupied Palestinian Territory.”[4]

When completed, the Annexation and Segregation Wall is going to be 712 kilometers long, which is more than twice the length of the Green Line,[5] and more than 9.4 percent of the West Bank and 30,000 Palestinians will be trapped between the Wall and the Green Line, an area now known as the seam zone.[6] The Human Rights Committee emphasized its concerns with the restrictions on freedom of movement imposed by the Annexation and Segregation Wall in its concluding observations on the fourth periodic report of Israel.[7]

Twelve years have passed since this judgment was made. Yet, Israel refuses to act upon any of these internationally-recognized obligations. To the contrary, Israel’s construction of the Wall continues steadily, and its associated regime of discriminatory legislation and practices remain firmly in place. The path of the Wall has resulted in the de-facto annexation of 9.4 percent of the West Bank.

But, the Wall is “only” yet another tool deployed by Israel to continue the process of colonizing Mandate Palestine (the geographical area which was ruled by the British Mandate, until its withdrawal in May of 1948: today, the state of Israel and the occupied Palestinian territory). Simply put, the Israeli endeavour aims at emptying Mandate Palestine from its indigenous inhabitants, including areas that lie, today, within the borders of Israel proper.

Related IMEMC report: 07/12/16 Israeli Settler State Created in West Bank, East Jerusalem

The intentionally designed displacement of Palestinians serves a parallel objective of relentlessly campaigning to settle Jewish-Israelis in colonies, illegal according to international law. In other words, Israel aims to colonize Palestine with Jewish immigrants (colonists) at the expense of the indigenous Palestinians, ultimately seeking to create a predominantly Jewish entity there as best described by Yosef Weitz, former director of the Land Department of the Jewish National Fund:

Between ourselves, it must be clear that there is no room for both peoples together in this country… There is no other way than to transfer the Arabs from here to neighboring countries – all of them. Not one village, not one tribe should be left.[8]

This colonization, today, is carried out, by Israel, in the form of the overall policy of ‘silent’ transfer, and not by the mass deportations witnessed in 1948 or 1967. It is silent in the sense that Israel carries it out, while trying to avoid international attention, displacing small numbers of people on a weekly basis. It is to be distinguished from the more overt transfer achieved under the veneer of warfare in 1948. Here it is important to note that Israel’s transfer policy is neither limited by Israel’s geographical boundaries, nor those of the occupied Palestinian territory.

The Israeli policy of silent transfer is evident in the state’s laws, policies and practices. Israel uses its power to discriminate, expropriate and ultimately effect the forcible displacement of the indigenous non-Jewish population from the area of Mandate Palestine. For instance, the Israeli land-planning and zoning system has forced 93,000 Palestinians in East-Jerusalem to build without proper construction permits because 87 percent of that area is off-limits to Palestinian use, and most of the remaining 13 percent is already built up.[9]

Since the Palestinian population of Jerusalem is growing steadily, it has had to expand into areas not zoned for Palestinian residence by the state of Israel. All those homes are now under the constant threat of being demolished by the Israeli army or police, which will leave their inhabitants homeless and displaced.

Another example is the government-approved Prawer Plan, which calls for the forcible displacement of 30,000 – 70,000 Palestinian citizens of Israel due to an Israeli allocation policy which has not recognized over thirty-five Palestinian villages located in the Naqab (Negev).[10]Israel deems the inhabitants of those villages as illegal trespassers and squatters, and, as such, they face the imminent threat of displacement. This is despite the fact that, in many cases, these communities predate the state of Israel itself.

The Israeli Supreme Court bolstered this objective of clearing Palestine of its indigenous population in its 2012 decision prohibiting family unification between Palestinians with Israeli citizenship and their counterparts across and beyond the 1949 Armistice Line. The effect of this ruling has been that Palestinians with different residency statuses -such as Israeli citizen, Jerusalem ID, West Bank ID or Gaza ID which all are issued by Israel- cannot legally live together on either side of the 1949 Armistice Line.

They are, thus, faced with a choice of living abroad, living apart from one another, or taking the risk of living together illegally.[11] Such a system is used as a further means of forcibly displacing Palestinians and thereby changing the demography of Israel and the occupied Palestinian territory in favor of a predominantly Jewish population. This demographic intention is reflected in the Court’s reasoning for its decision, where it stated that “…human rights are not a prescription for national suicide.”[12] This reasoning was further emphasized by Knesset-member Otniel Schneller who stated that “The decision articulates the rationale of separation between the [two] peoples and the need to maintain a Jewish majority…and character…”.[13]

This illustrates, once more, the Israeli state’s self-image as a “Jewish State” with a different set of rights for its Jewish and non-Jewish, mainly Palestinian, inhabitants.

Related IMEMC: 01/06/16 Democracy: ‘Disastrous for the Jewish People’

Separation and conquest

The enterprise of colonizing Palestine is deeply rooted in the principle of separation and conquest. The idea of “constructing a Wall” started with the first Zionist colonists groups entering Palestine in the beginning of the 20th Century. Kibbutzim were the first form of creating “little fortresses” in an unknown and hostile environment as seen by the Zionist colonists.

The kibbutz, a collective community, was formed by European Jews to conquest Palestinian land and to separate the conquered land from its indigenous Palestinian inhabitants in order to establish a territory for the Jewish people. In this regard, Kibbutzim even “rejected” the exploitation of cheap Arab labor and used instead Yemenite Jewish agricultural workers.[14] This politics of separation and conquest is still visible today in various aspects and throughout all of Mandate Palestine.

Israeli cities in the Galilee or Israeli colonies in the West Bank resemble the architecture of “fortresses”. They are created on hilltops, completely encapsulated with only one or two streets leading to them, and their surroundings resemble a moat of trees and stones and impenetrable passages. It is also visible in Jerusalem, where the Wall is created by discriminatory state and municipality practices and services. Palestinian neighborhoods are denied proper infrastructure or development, contrary to Israeli Jewish colonies and neighborhoods in Jerusalem: although the Palestinian community in Jerusalem represents 35 percent of the city’s population, and pays higher taxes than their Jewish Israeli counterparts, they receive less than 10 percent of the municipal budget.[15]

Another example is the Palestinian city of Jericho, where the city is encircled by an invisible Israeli wall which prohibits the city of its natural growth. The city’s outskirts are part of the Area C of the West Bank where Israel virtually eliminates the possibility for further construction and development;[16] and therefore separates the city from its own environment.

Therefore, the Wall is not only built by concrete stone, it is seeded in the Zionist ideology of separation and conquest.

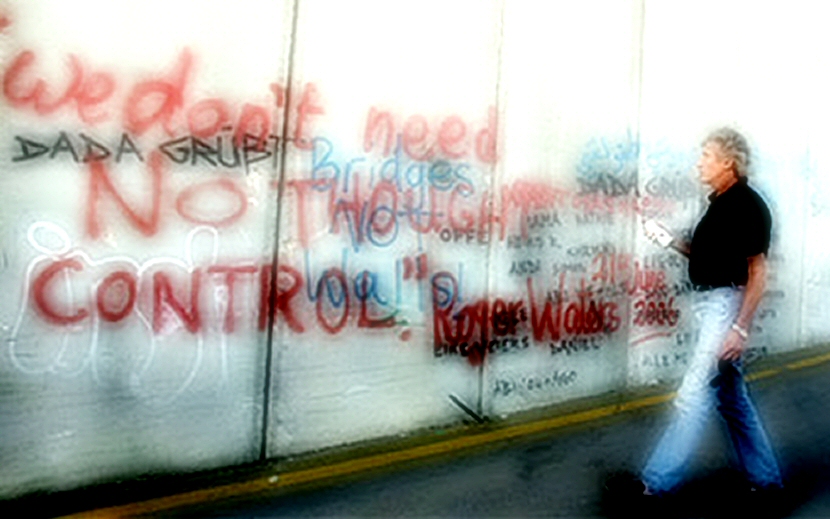

photo: Protestors promote boycott of Israeli products at a section of the Wall in Bethlehem. (PNN archives.)

Also in IMEMC Opinion/Analysis: The Impossibility to Know – Navigating the Psychological Siege of Hebron

About the author:

Amjad Alqasis holds a LL.M. in international public law and is a legal researcher and a member of the Legal Support Network of BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights. From 2011-2014 he was the coordinator of BADIL’s international and legal advocacy program. Since August 2014, Amjad has been an advisor at Al Haq Center for Applied International Law. He has published several articles and researches on various topics concerning the Palestinian-Israeli conflict.

IMEMC Editor: chris @ imemc.org

[1] OCHA – Occupied Palestinian Territories, “Barrier Portal”, 2014. Available at: http://www.ochaopt.org/content.aspx?id=1010271

[2] OCHA – Occupied Palestinian Territories, “10 Years since the International Court of Justice (ICJ) Advisory Opinion”, 9 July 2014, page 2. Available at: http://www.ochaopt.org/documents/ocha_opt_10_years_barrier_report_english.pdf

[3] International Court of Justice, “Legal Consequences of the Construction of the Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Advisory Opinion, ICJ Reports 2004”, 9 July 2004. Available at: http://www.icj-cij.org/docket/index.php?pr=71&code=mwp&p1=3&p2=4&p3=6&ca.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ma’an News Agency, “Israel court rules against separation wall in Beit Jala”, 2 April 2015. Available at: https://www.maannews.com/Content.aspx?id=760247

[6] HaMoked – center for the Defence of the Individual, “The Permit Regime: Human Rights Violations in West Bank Areas Known as the ‘Seam Zone’”, March 2013, pages 5 & 9. Available at: http://www.hamoked.org/files/2013/1157660_eng.pdf

[7] UN Human Rights Committee, “Concluding observations on the fourth periodic report of Israel (Advance Unedited Version)”, October 2014, page 7. Available at: http://www.ccprcentre.org/doc/2014/10/CCPR_C_ISR_CO_41.doc

[8] Joseph Weitz, Davar, September 29, 1967, cited in Uri Davis and Norton Mevinsky, eds., Documents from Israel, 1967-1973, p.21.

[9] OCHA-OPT, Demolitions and Forced Displacement in the Occupied West Bank (2012).

[10] See Adalah, “The Prawer Plan and Analysis” (October 2013), at:http://www.adalah.org/upfiles/2011/Overview%20and%20Analysis%20of%20the%20Prawer%20Committee%20Report%20Recommendations%20Final.pdf.

[11] See HCJ 466/07, MK Zahava Galon v. The Attorney General, et al. (petition dismissed 11 January 2012).

[12] Ben White, “Human rights equated with national suicide”, Aljazeera (12 January 2012) at:http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2012/01/20121121785669583.html.

[13] Ibid.

[14] See Uri Ram, The Changing Agenda of Israeli Sociology: Theory, Ideology, and Identity,SUNY Press, 2012.

[15] See the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs at: http://www.ochaopt.org/.

[16] Ibid.